THE GREAT HERRING WHAT?

Thursday, December 25, 2025

Friday, November 14, 2025

If you're interested--Swedish pickled herring:

The following is excerpted from " Easy Swedish Pickled Herring- And its Long History"

(https://swedishspoon.com/pickled-herring/):

....Yes, that’s a line in the famous ABBA song, but in Sweden, it could also be a (somewhat rude) call to someone for a small meal.

The letters in S.O.S stand for smör, ost, and sill — butter, cheese, and herring. You eat this trio on hard bread and often rinse down with a shot of schnapps. You’ll often find this way of serving herring as a starter in traditional restaurants.

Wednesday, November 12, 2025

Shoo-Be-Do-Be-Doo:

A New Herring Experience

Last week at

our friend Cara’s house we feasted on Shuba—a Russian dish known as “herring

under a fur coat”. It was a first time for me--a whole new way to enjoy

herring!!! It looked like a birthday cake and it made me think of Stevie Wonder’s

song on the way home

Here are 2

recipes:

https://momsdish.com/recipe/132/shuba-fur-coat-salad#jump-to-recipe

https://www.jewishfoodsociety.org/recipes/shuba-russian-herring-salad

Saturday, October 18, 2025

Friday, September 5, 2025

Friday, August 22, 2025

Tuesday, May 27, 2025

She has very nice recipes and writes great cookbooks, but I don't think her palate has matured in the decade since this article came out: " if savoring herring is the ticket into heaven, then I am most certainly doomed." 😎

Source: https://forward.com/food/317978/beyond-the-bagel-herring-not-a-love-story/

By Leah KoenigJuly 27, 2015

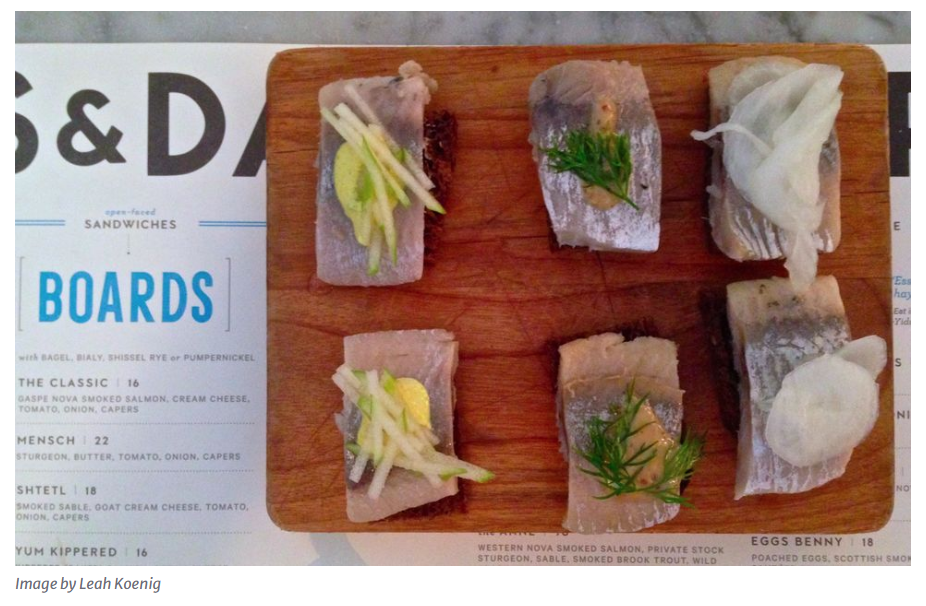

A trio of pickled herring on pumpernickel from Russ & Daughters Café (above) may be an exemplary version of the classic Eastern-European breakfast staple — but it couldn’t convince our author to give up her intense dislike of the stuff.

I want to love herring. I do. The oily little fish are healthy (packed with fatty acids), relatively sustainable and, most relevant to my purposes, one of the hallmarks of Eastern European Jewish cuisine. Pickled herring on brown bread sustained my ancestors for generations. And served with kichel (egg cookies) and a shot of schnapps, they were once the center of the .

There is one problem. I hate herring — I really, really do. Over the years, I have dutifully tried it over and again, pickled with onions, steeped in wine and coated in cream. And each time, it sets off gag reflexes. It’s just too pungent, too fishy, too much. My response brings shame to my name as a food writer and dashes any dreams I might harbor of one day retiring to Boca Raton.

Strangely, despite my own culinary aversions, I fully support the diminutive little critters. I love that herring is enjoying something of a comeback, and I would happily proclaim it the ideal Jewish breakfast food — as long as I do not have to personally eat it.

In soul, if not in body, I am on Team Herring.

Last Friday, my husband, Yoshie, and our 1-year old, Max, and I ate breakfast at the Russ & Daughter’s Café — the year-old outpost of the esteemed, century-old appetizing shop on New York’s Lower East Side. The café brings to life the lost tradition of New York’s grand dairy restaurants, serving blintzes with fruit compote, kasha varnishkes, chilled borscht with sour cream and a dream lineup of cured salmon, smoked sable and, naturally, pickled herring. Even the marble floor, one of many gorgeous, vintage design elements in the cafe, has a herringbone pattern.

If there were anywhere that could convince me to tolerate (I won’t even pretend to say “love”) herring, it would be Russ & Daughters. So along with a plate of latkes, a Super Heebster bagel (topped with an unorthodox but remarkably delicious mix of whitefish salad, horseradish dill cream cheese, and wasabi-infused roe), a bowl of delicate, smoked whitefish chowder and a plate of lox, eggs and onions, we ordered a trio of pickled herring on pumpernickel.

I worked my way around the table, crunching my fork into the latkes, spooning bites of whitefish towards Max and eyeing the pretty plate of canapés sitting just to my right. The fish glistened with pearly iridescence. It was fatty and fleshy. I asked Yoshie to try them first. “It’s really great herring,” he said, chewing thoughtfully. “But it is definitely herring.”

Then he fed some to Max, who showed up his mother by happily gobbling two slippery hunks of the stuff. As the meal dwindled, the pressure began to build. How could I pass by the opportunity to try what is almost certainly the best herring in the city? How could I look my husband and baby boy in the eyes and then cave to my weak taste buds?

Taking a deep breath, I took half a herring canapé layered with mustard and shredded apple, thinking the formidable toppings might mask the fishy flavor. I chewed minimally and swallowed quickly. I may have eaten the entire bowl of applesauce from the latke platter as a chaser.

The verdict? I’ll leave it at this: I will remember our breakfast at Russ & Daughters Café as elegant, nostalgic without an ounce of kitsch and inimitably delicious. But if savoring herring is the ticket into heaven, then I am most certainly doomed.

Monday, May 26, 2025

Tuesday, May 20, 2025

Friday, April 18, 2025

Thursday, March 27, 2025

A STORY FOR YOU HERRING LOVERS OUT THERE 💓

In fact, so great was our disgust with the smelly,

slithering fish, that for a while, we made my father eat the herring outside.

In the New York winter. In the snow.

While herring never touched my lips for the first 30 years

of my life, I knew things about herring, just like a child who

grows up in the schmatte business knows a thing or two about exports and

imports. For example, I knew that not all herring is created equal. In fact,

herring is so varied that a man’s choice in herring is nothing less than a

window to his soul, a way of showing the world whether he is a kind,

philosophical man, or a bore who never once stopped to smell the flowers. In

the class hierarchy of herring, I was taught that matjes, my family’s choice,

was for the classy, discerning, sophisticated people; pickled was for people

who, though good and upright, did not have the finest taste; and schmaltz—God

forbid, schmaltz—was for the shtetl folks, the peasant people who

temperamentally are simply not able to discriminate.

Whether it’s true or not, I accepted the wisdom that herring

was just another one of the Eastern European Jewish foods destined to fade away

from modern cuisine, becoming the provenance of a small group of passionate

connoisseurs. It was to be relegated to that dusty shelf, to sit

alongside ptcha—warm,

garlic jelly made out of calves’ feet—and kishka, stuffed derma so high in fat

that the USDA classification system can barely categorize it. As far as my

palate was concerned, I could have gone on living my life content without

herring, even learning to make a certain peace with it, like an American in

England watching people eat marmite—tolerant, if not a little disdainful.

But after years of theatrically gagging upon seeing my

father eat herring, I gave in. For the first time, at age 30, I tasted it.

It was one of those Saturday mornings when I happened to be

home. My father took out the herring; I made a horrified face. He said, “Shira,

you like sushi right?” I nodded. “And sushi is raw fish?” I nodded,

increasingly aware that I was being backed into a logical corner from which

there would be no escape. My father continued: “Well, herring is raw fish also,

just cured with spices, salt, and oil.” Now, I can recognize a good, logical

argument when I hear one. I like—no, I love—sushi. Sushi is like herring.

Therefore, perhaps, I loved herring?

I pierced the herring with a fork. I lifted it to my mouth

with the ceremony of someone taking an elixir that, though vile, must be

imbibed. I dropped it into my mouth.

It was intense. Acidic and biting, yet soft, almost

meltingly tender. Sweet but salty, robust yet elusive. After my first bite, I

was confused. The herring wasn’t necessarily delicious, but it was undeniably

intriguing. It was as if herring was unknowable, so perplexing and disarming a

combination of tastes that it was addictive by sheer virtue of its mystery. And

I wanted to, well, know it again. So, I took a second piece.

More flavors, more contradictions. Suddenly, after years of dismissing this

modest fish, I understood my father’s passion for it, the artisan and poet’s

search for the beauty and perfection that is found in a good piece of fish.

That’s how, in a matter of minutes, after a lifetime of

forswearing this particular food, I came to sit down with my father at the same

herring table. These days, when Saturday mornings arrive and I am at my

parents’ house, I join my father in his weekly ritual, as we carefully open the

lid of the herring container and eagerly await the first taste of our beloved

fish. Will this week’s vintage be too salty, too oily, or will it achieve

herring nirvana, that perfect harmony of spices and wine?

Recently I asked my father how he felt about my herring

turnaround. “It was the happiest day of my life,” he answered, jokingly. “The

only thing better will be your wedding day.” But I know he’s delighted about

it, and I can detect a new enthusiasm in the texts and emails he sends before

visiting me in D.C. “Mommy and I are going now to buy the herring,” he’ll

write. “How much do you want? And if they have herring in cream, do you want to

try that also?”

These days, when my father and I sit down to eat herring, my

young nephew is the one who looks at the shiny, pink fish and wrinkles his

nose. Like my father used to do, I dismiss this child with a laugh and a wave

of my hand, knowing that in 20 years time, he’ll be sitting with us at the

table.

(In the meantime, the annual “new

catch” Holland herring arrives next week, promising herring nirvana for

everyone.)

Sunday, March 23, 2025

Saturday, March 22, 2025

Thursday, January 30, 2025

OK- LETS GO TO HERRING SCHOOL!! 🐟

So, what is herring anyway? Yes, most people know that herring is a fish, but many don’t get further than that. Some may go on to describe herring as a small fish. This is also correct. As a close relative of the sardine and the shad, herring is indeed a smaller fish. Herring might have the reputation of being a “fish” like any other, but we would argue that it achieves a bold and assertive flavor profile when it is pickled.

It’s fascinating that people don’t know more about this small but mighty fish, so we’re here to arm you with all that there is to know about the hardy herring! Who knows, maybe this will motivate you to venture out of your comfort zone and try it, if you haven’t already. Trust us, you won’t be disappointed!

FOR THE WHOLE STORY ON ACME'S YUMMY HERRING, READ THIS:

https://acmesmokedfish.com/blogs/news/meet-the-herring-a-glossary-of-herring-varieties